Acute Liver Failure

The following article lists some simple, informative tips that will help you have a better experience with Acute, Failure, Liver.

Now that we’ve covered those aspects of Acute, Failure, Liver, let’s turn to some of the other factors that need to be considered.

Acute liver failure (ALF), also known as fulminant hepatic failure, is a rare manifestation of liver disease and constittes a medical emergency.

The syndrome arises from loss of hepatic parenchyma that may result from a variety of insults to the liver.

Despite advances in medical management and the availability of liver transplantation, mortality rates in patients with ALF remain substantial. It has been estimated that in the United States, 2000 deaths a year are attributable to ALF.

Definition:

ALF has been defined by three criteria: (1) rapid development of hepatocellular dysfunction (e.g., jaundice, coagulopathy), (2) encephalopathy, and (3) absence of a prior history of liver disease

ALF originally was defined by an interval between the onset of illness and appearance of encephalopathy of 8 weeks or less,but there is marked heterogeneity among affected patients with respect to the temporal progression of disease.

Definition:

The time course of ALF has etiologic, biologic, and prognostic significance. For example, an illness of 1 week or less before the development of encephalopathy is characteristic of ALF caused by hepatic ischemia or acetaminophen toxicity.

In contrast, an interval longer than 4 weeks is more likely to be caused by viral hepatitis or ALF of unknown etiology.

Definition:

Patients with a duration of illness longer than 2 weeks before the onset of encephalopathy have a higher likelihood of developing manifestations of portal hypertension, such as ascites or renal failure.

Definition:

Some investigators have suggested that the term fulminant hepatic failure be reserved for cases in which encephalopathy develops within 2 weeks of the onset of jaundice and that the term subfulminant hepatic failure be applied to cases in which encephalopathy develops between 2 weeks and 3 months of the onset of jaundice

Others have proposed that ALF be redefined to comprise three distinct syndromes:

Definition:

Hyperacute liver failure (onset of encephalopathy within 1 week of jaundice), acute liver failure (development of encephalopathy between 1 and 4 weeks of jaundice), and subacute liver failure (development of encephalopathy within 5 to 12 weeks of jaundice).

Unfortunately, there is great overlap in prognosis among patients with varying presentations, regardless of which nomenclature is used. Moreover, no universally accepted nomenclature has yet been adopted.

Causes:

The most common causes of ALF are :

Drugs

Hepatotropic viruses

However, many other conditions can lead to ALF, albeit uncommonly . Despite serologic and molecular advances in the diagnosis of viral infections, ALF of unknown etiology continues to represent a substantial proportion of the patients affected by this syndrome .

Drugs:

Most cases of drug-related ALF result from acetaminophen overdose. In fact, acetaminophen is the most common single cause of ALF .

Acetaminophen is directly hepatotoxic and predictably produces hepatocellular necrosis with an overdose (>12 g). Because of its easy availability, acetaminophen is a common mode of suicide and, occasionally, a cause of unintentional overdose.

Drugs:

Even recommended therapeutic dosages of acetaminophen (as low as 4 g) can sometimes result in ALF in patients who are fasting or who chronically use alcohol or drugs that induce cytochrome oxidases .

Numerous other drugs, including halothane, isoniazid, valproate, sulfonamides, phenytoin, thiazolidinediones, and certain herbal remedies, have been implicated in ALF. In most cases, drug-related ALF is rare and idiosyncratic.

Hepatotropic Viruses:

Hepatitis A and hepatitis B viruses are major causes of ALF .

Infection with hepatitis A virus (HAV) rarely leads to ALF, and when it does, the prognosis is relatively good.

. Although hepatitis B virus (HBV) is the most common viral cause of ALF , ALF is an uncommon manifestation of HBV infection.

Hepatotropic Viruses:

Infection with hepatitis D virus (HDV) requires coinfection with HBV. In certain geographic regions, HDV can account for almost 5% of the cases of ALF in patients who are positive for hepatitis B surface antigen and approximately 4% of the cases of ALF in patients who are positive for IgM antibody to hepatitis B core antigen.

Acute Liver Failure of Unknown Etiology

ALF of unknown etiology, defined by negative serologic testing for hepatitis A and B and the absence of other known causes, constitutes 15% to 44% of the total cases of ALF .

It had been anticipated that new sensitive molecular methods such as the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) would identify a viral etiology for ALF of unknown cause, but most cases remain cryptogenic.

Acute Liver Failure of Unknown Etiology

Although hepatitis C virus (HCV) has been implicated as a cause of ALF in a few patients, it appears that HCV is an exceedingly rare cause of ALF in Western countries. In Japan, however, HCV may be a more common cause of ALF.

Hepatitis E virus (HEV), an acknowledged cause of ALF in central Asia and other parts of the developing world, has not been found to cause ALF in the United States or the European continent.

Acute Liver Failure of Unknown Etiology

Despite the identification of hepatitis G virus (HGV) in patients with ALF of unknown etiology, HGV does not appear to cause ALF.

Several other viruses merit comment. Togavirus-like particles have been identified by electron microscopy in 7 of 18 liver explants from patients who underwent transplantation for ALF but are unlikely to be responsible for a substantial portion of these cryptogenic cases. The TT virus has been found in patients with ALF in the United States and Japan, but it is uncertain whether this virus can cause ALF.

Acute Liver Failure of Unknown Etiology

Finally, parvovirus B19 has been postulated to be an important cause of ALF, but this postulate remains to be verified .

Although these viruses warrant further investigation as causes of ALF, it is doubtful that any of these viral causes will explain the etiology of a significant portion of the cases of cryptogenic ALF.

Clinical Presentation:

The initial presentation of ALF may include nonspecific complaints such as nausea, vomiting, fatigue, and malaise, but jaundice develops soon after .

Hepatocellular Dysfunction:

Hepatocellular injury or loss leads to impaired elimination of bilirubin .

depressed synthesis of coagulation factors I, II, V, VII, IX, and X; diminished glucose synthesis; and decreased lactate uptake or increased generation of intracellular lactate as a result of anaerobic glycolysis.

Clinical Presentation:

These derangements manifest clinically as jaundice, coagulopathy, hypoglycemia, and metabolic acidosis, respectively.

Hepatic Encephalopathy and Cerebral Edema

Encephalopathy is a defining criterion for ALF

The severity of encephalopathy can range from subtle changes in affect, insomnia, and difficulties with concentration (stage 1); to drowsiness, disorientation, and confusion (stage 2); to marked somnolence and incoherence (stage 3); to frank coma (stage 4).

Clinical Presentation:

The pathophysiologic mechanisms underlying ALF-associated encephalopathy are multifactorial.

Many features of ALF, including hypoglycemia, sepsis, hypoxemia, occult seizures, and cerebral edema, can contribute to neurologic abnormalities.

Continuous monitoring of cerebral activity by electroencephalogram (EEG) identifies subclinical seizures in almost 33% of ALF patients with at least stage 3 encephalopathy who are mechanically ventilated and paralyzed.

Clinical Presentation:

Cerebral edema is found in up to 80% of patients who die in the setting of ALF and is virtually universal among patients with coma .

Progressive cerebral edema will produce intracranial hypertension, which results in cerebral hypoperfusion and irreversible neurologic damage .

The pathogenesis of cerebral edema in ALF is poorly understood. It has been proposed to result from the actions of gut-derived neurotoxins that escape hepatic clearance and are released into the systemic circulation.

Clinical Presentation:

Two principal mechanisms appear to contribute to the development of cerebral edema in this setting: brain cell swelling (cytotoxic edema) and disruption of the blood-brain barrier (vasogenic edema).

Progressive cerebral edema can impair cerebral perfusion, which may lead to irreversible neurologic damage or even result in uncal herniation and death .

Clinical Presentation:

Infection

Infections develop in as many as 80% of patients with ALF, and bacteremia is present in 20% to 25%.

Uncontrolled infection accounts for approximately 25% of patients with ALF who are excluded from liver transplantation and approximately 40% of postoperative deaths.

Clinical Presentation:

At least three factors place patients with ALF at increased risk for infection. First, gut-derived microorganisms may enter the systemic circulation from portal venous blood as a result of damage to hepatic macrophages (Kupffer cells).

Second, impaired neutrophil function may result from reduced hepatocellular synthesis of acute-phase reactants, such as components of the complement cascade.

Clinical Presentation:

Third, patients with ALF are often subjected to invasive procedures (e.g., intravascular and urethral catheterization, endotracheal intubation), and physical barriers to infection, including skin and airway, are thus breached.

the major sites of infection are the respiratory and urinary tracts.

It is not surprising therefore that the most common bacteria isolated are staphylococcal and streptococcal species and gram-negative rods.

Clinical Presentation:

Fungal infections develop in up to one third of patients with ALF.

The majority of these infections are caused byCandida albicans. Although Aspergillus infections have been thought to be uncommon in the setting of ALF.

Risk factors for fungal infections are renal failure and prolonged antibiotic therapy for bacterial infections.

Characteristically, fungal infection is associated with fever or leukocytosis refractory to broad-spectrum antibiotics.

Clinical Presentation:

Gastrointestinal Bleeding.

Patients with ALF have an increased risk of hemorrhage because of deficiencies in coagulation factors and thrombocytopenia.

Such critically ill patients thus have a propensity for gastrointestinal stress ulceration and consequent bleeding.

In contrast to patients with chronic liver failure, those with ALF rarely exhibit bleeding from varices.

Clinical Presentation:

Multiple Organ Failure Syndrome

A potential consequence of ALF is the syndrome of multiple organ failure .

This syndrome manifests clinically as peripheral vasodilation with hypotension, pulmonary edema, acute tubular necrosis, and disseminated intravascular coagulation.

Multiple organ failure is a significant contributor to patient mortality and a major contraindication to liver transplantation.

Clinical Presentation:

For example, acute tubular necrosis is associated with a 50% decrease in survival among patients with acetaminophen-induced ALF, and the mortality rate is more than doubled in patients with multiple organ failure.

Respiratory failure commonly is associated with ALF. In one series, 37% of patients with ALF had pulmonary edema.

In another study, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) was present in 33% of patients with acetaminophen-associated ALF.

Clinical Presentation:

The cause of renal failure in ALF (seen in more than one third of patients in one series) is multifactorial.

Hepatorenal syndrome is often difficult to differentiate from intravascular volume depletion, which is also a common finding in ALF.

Acute renal tubular acidosis is a prominent component of multiple organ failure syndrome .

Differential Diagnosis:

The differential diagnosis includes sepsis, preeclampsia/eclampsia, and an acute decompensation of chronic liver disease.

In particular, both sepsis and ALF have similar hemodynamic pictures, with decreases in peripheral vascular resistance accompanied by high cardiac output.

Encephalopathy, a hallmark of ALF, also may be a manifestation of the sepsis syndrome.

Differential Diagnosis:

If the hepatic manifestations of sepsis are severe, the clinical picture can be mistaken for ALF .

Measurement of levels of factor VIII, which is not synthesized by the liver, may be helpful in differentiating sepsis (low factor VIII level) from ALF (factor VIII level generally not suppressed .

In the pregnant patient, preeclampsia/eclampsia also can be difficult to differentiate from ALF, particularly ALF resulting from fatty liver of pregnancy.

Differential Diagnosis:

an acute exacerbation of liver dysfunction in patients with underlying chronic liver disease is occasionally confused with ALF.

Examples include alcoholic hepatitis in patients with alcoholic cirrhosis and flares of chronic viral hepatitis.

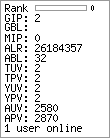

Predictors of outcome:

Patients with ALF fall into two broad categories:

(1) those in whom intensive medical care enables recovery of hepatic function

(2) those who require liver transplantation to survive

Thus, it is critical to determine rapidly the group into which a particular patient may belong. It is also critical to avoid the following two scenarios:

(1) death of the patient despite intensive medical care without consideration of transplantation .

Predictors of outcome:

(2) unnecessary liver transplantation when recovery would have occurred spontaneously.

The etiology of disease and clinical presentation have predictive relevance

For example, patients with ALF caused by hepatitis A have a better prognosis than those with ALF of unknown etiology.

Patients who reach stage 3 or stage 4 encephalopathy tend to do worse than those who reach only stage 1 or stage 2.

Predictors of outcome:

However, these indicators do not allow accurate prediction of the need for transplantation .

The most extensive analysis has been performed by investigators at King’s College in London.

These investigators performed a multivariate analysis of clinical and biochemical variables and their relation to mortality in 588 patients with ALF.

Predictors of outcome:

The following characteristics were associated with a poor outcome:

negative serology for hepatitis A or B, younger (40 years) age, prolonged duration of jaundice, markedly elevated serum bilirubin level, marked prolongation of the prothrombin time, and in patients with acetaminophen toxicity, arterial acidosis, and an elevated serum creatinine level.

Those who only know one or two facts about Acute, Failure, Liver can be confused by misleading information. The best way to help those who are misled is to gently correct them with the truths you’re learning here.